| |  Web Content Display

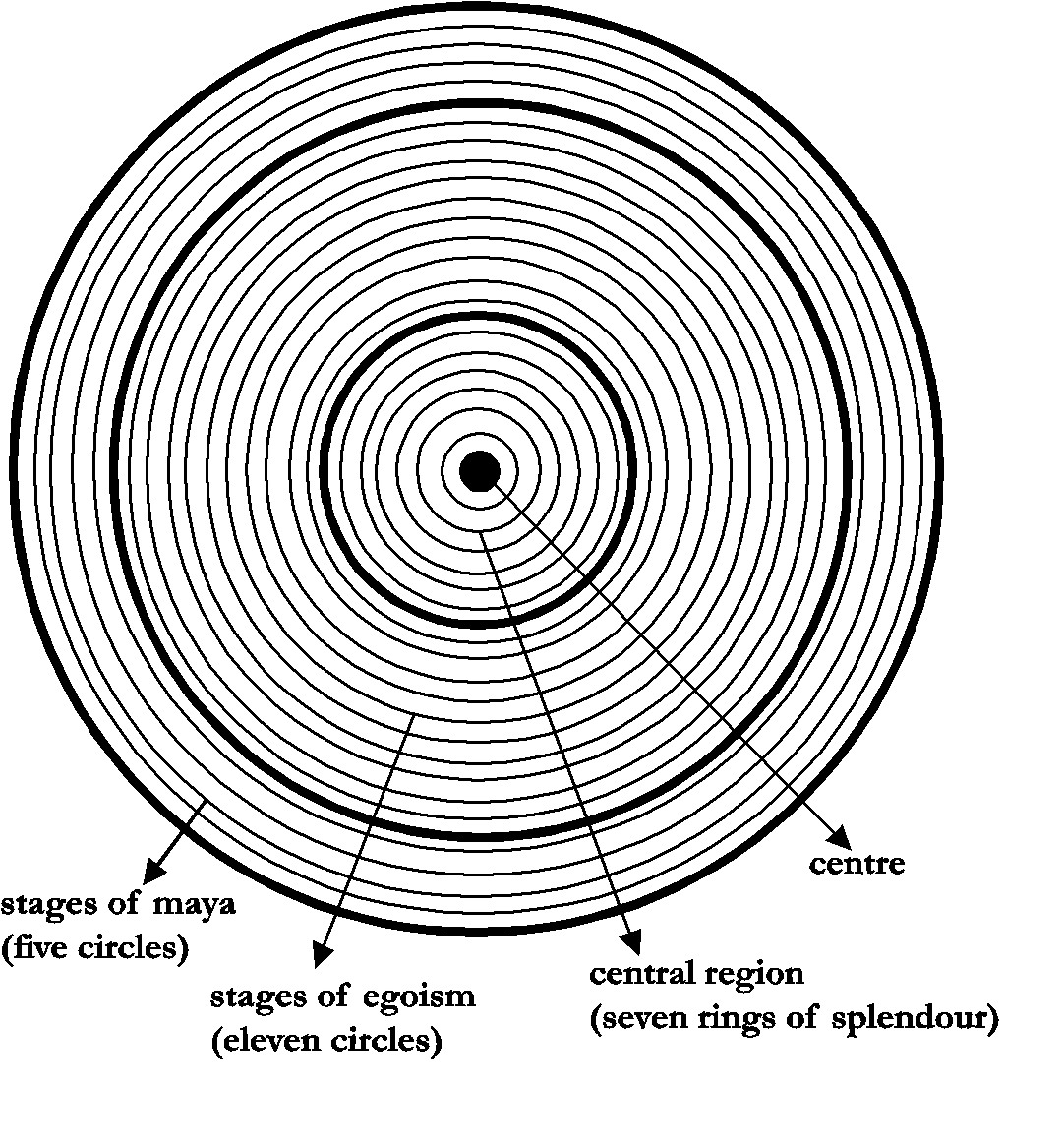

Web Content Display The Goal of LifeThis article is an excerpt from “Reality At Dawn”. For further reading, please order a copy of the book on the digital store There are perhaps only a few among the masses who have ever given any serious consideration to the problem of life. Generally, they take a very narrow view of it. The only problem before them is to secure a decent living, well provided with the desired comforts. In other words, to them the object of life is only to achieve the greatest possible comfort and prominence in the world. If they are able to achieve it, they think their life to be a success, otherwise not. They may, however, pass on as great men, philosophers, scientists or politicians and acquire worldwide fame and riches, but their problem of life still remains unsolved. It does not really end with death, for it is only a change of form. Our next life, whatever it may be, begins after death. Just as prior to our present life we have had numerous other lives in different forms, similarly even after our death we may have numerous other lives. The cycle of birth and death continues indefinitely. The problem before us is not to find out a solution of our present life, but for all lives that we may henceforth have. In the wider sense, it covers the entire existence of soul in various forms, gross or subtle, at different times till the time of mahapralaya (final extinction). There may be differences of opinion over the question of births and deaths among the followers of different creeds, but it is certain that mere theoretical knowledge of the scriptures will not solve the question. Practical experience in the spiritual field is necessary for the purpose. The question ends when one acquires anubhava Shakti (intuitive capacity) of the finest type and can himself realise the true state of life hereafter. The mystery is, however, explained by people in various ways, but almost all agree on the point that the object of life is to achieve eternal bliss after death. For this they insist on a life of virtue, sacrifice and devotion, which will bring to them the eternal joy of paradise or salvation or peace. But that is not the end of the problem. It goes on much beyond. Now in order to trace out the solution of the problem, we must look back to the point wherefrom our existence has started. Our existence in the present grossest form is neither sudden nor accidental, but it is the result of a slow process of evolution. The existence of the soul can be traced out as far back as to the time of creation, when the soul existed in its naked form as a separate entity. From that primary state of existence of the soul in its most subtle form, we marched on to grosser and grosser forms of existence. These may be expressed as coverings around the soul. The earliest coverings were of the finest nature, and with them we existed in our homeland – the Realm of God. The additions of more and more coverings of ego continued, and subsequently manas (psyche), chit (consciousness), buddhi (intellect) and ahamkara (ego) in cruder forms began to contribute to our grossness. In due course, samskaras (impressions) began to be formed, which brought about their resultant effects. Virtue and vice made their appearances. Slowly, our existence assumed the densest form. The effect of samskaras is the commencement of feelings of comforts, miseries, joys and sorrows. Our likings for joys and comforts and our dislikings for sorrows and miseries have created further complications. We generally find ourselves surrounded with pain and misery, and we think that deliverance from them is our main goal. This is a very narrow view of the problem. The aims and objects of life conceived in terms of worldly ends are almost meaningless. We forget that pains and miseries are only the symptoms of a disease, but the disease lies elsewhere. To practise devotion to please God in order to secure worldly comforts or gains is but a mockery. The problem before us is not mere deliverance from pain and misery but freedom from bondage, which is the ultimate cause of pain and misery. Freedom from bondage is liberation. It is different from salvation, which is not the end of the process of rebirth. Salvation is only a temporary pause in the rotation. It is the suspension of the process of birth and death only for a certain fixed period, after which we again assume the material form. The endless circle of rebirth ends only when we have secured liberation. It is the end of our pains and miseries. Anything short of liberation cannot be taken as the goal of life, although there remains still a lot beyond it. We find but a few persons who have even liberation as the final goal of their life, which represents the lowest rung in the spiritual flight. The problem of life remains totally unsolved if we are below this level. There are persons who may say that they do not want mukti (liberation). They only want to come again and again into this world and practise bhakti (devotion). Their goal of life is undetermined and indefinite. Bhakti and nothing beyond, as they say, is their goal. Really, they are attracted by the charming effect of the condition of a bhakta (devotee) and like to remain entangled in it forever. They do it only to please themselves. Freedom from eternal bondage is not possible so long as we are within entanglements. The natural yearning of soul is to be free from bondage. If there is one who does not like to free himself from the entanglements, there is no solution for him. Bhakti is the means of achieving the goal and not the goal itself. The fact, as I have stated above, is that they are allured by the charming effect of the primary condition and do not want to get away from it at any time. The narrow view that they have taken bars their approach to a broader vision, and anything beyond is out of their sight. Another fallacious argument advanced in support of the above view is that devotion, if practised with any particular object in view, is far from being nishkama (desire less). The theory of nishkama upasana (desire less devotion) as laid down in the Gita emphasises upon us to practise devotion without keeping in view any specific purpose. It really means that we should practise devotion without our eyes being fixed upon any worldly object or without caring for the satisfaction of our desires. It does not stop us from fixing our mind upon the goal of life, which is absolutely essential for those on the march. The goal of life means nothing but the point we have finally to arrive at. It is, in other words, the reminiscence of our homeland, or the primeval state of our present solid existence which we have finally to return to. It is only the idea of destination which we keep alive in our minds, and for that we practise devotion only as duty. Duty for duty’s sake is without doubt nishkama karma (selfless action), and to realise our goal of life is our bounden duty. Now I come to the point of what the real goal of life should be. It is generally admitted that the goal must be the highest, otherwise progress up to the final limit is doubtful. For this, it is necessary to have a clear idea of the highest possible limit of human approach. We have before us the examples of Rama and Krishna, the two incarnations of Divinity. We worship them with faith and devotion and want to secure union with them. Automatically that becomes our goal of life, and we can at the utmost secure approach up to their level. Now Rama and Krishna, as incarnations, were special personalities vested with supernatural powers to work as a medium for the accomplishment of the work which Nature demanded and for which they had come. They had full command over the various powers of nature and could utilise them at any time in a way they thought proper. The scope of their activity was limited in accordance with the nature of the work they had to accomplish. They descended from the sphere of Mahamaya, which is a state of Godly energy in the subtle form, hence the most powerful. It is due to this fact that we find excellent results coming into effect through their agency in their lifetime. The highest possible point of human approach is much beyond the sphere of Mahamaya, hence a good deal above that level. It may be surprising to most of the readers, but it is a fact beyond doubt. The final point of approach is where every kind of force, power, activity or even stimulus disappears and a man enters a state of complete negation, Nothingness or Zero. That is the highest point of approach or the final goal of life. I have tried to express it by the diagram. The concentric circles, drawn round the centre, ‘C’, roughly denote the different spiritual spheres we come across during our progress. Beginning our march from the outermost circle, we proceed towards the centre, crossing each circle to acquire the next stage. It is a very vast expanse. If I speak of liberation, people will think it to be a very far-off thing which can be achieved by persistent efforts for a number of lives. In the diagram, the state of liberation lies between the second and the third circles. The various conditions we have to pass through in order to secure liberation are all acquired within about a circle and a half. This may help the reader to form a rough idea of what still remains to be achieved after we have reached the point of liberation, which really, as commonly believed, is not an ordinary achievement. After achieving this state, we go on further, crossing other circles till we cross the fifth one. This is the stage of avyakta gati (undifferentiated state). At this stage a man is totally free from the bounds of maya. Very few of the sages of the past could reach up to this position. Raja Janak was one of those who could secure his approach to this state. His achievements were considered to be so great that even the prominent rishis (sages) of the time used to send their sons and disciples to him for training. The region of Heart as described in my book Efficacy of Raja Yoga is now crossed, and now we enter the Mind Region after crossing the fifth circle. The eleven circles after this depict the various stages of egoism. The condition there is more subtle and grows finer still as we march on through the region. By the time we reach the sixteenth circle, we are almost free from egoism. The condition at this stage is almost inconceivable and has rarely been attained by even the greatest of sages. As far as my vision goes, I find among the ancient sages none except Kabir who could have secured his approach up to this stage (i.e. the sixteenth circle). What remains when we have crossed this circle is a mere identity, which is still in a gross form. We now enter the Central Region. There, too, you will find seven rings of something, I may call it light for the sake of expression, which we cross during our march onwards. The form of dense identity, as I have called it, grows finer and subtler to the last possible limit. We have now secured a position which is near most to the Centre, and it is the highest possible approach of man. There we are in close harmony with the very Real condition. Complete merging with the Centre is, however, not possible, so as to maintain a nominal difference between God and soul. Such is the extent of human achievement which a man should fix his eyes upon from the very beginning, if he wants to make the greatest progress on the path of realisation. Very few among the saints and yogis of the world ever had any conception of it. Their farthest approach in most cases had been up to the second or the third circle at the utmost, and it is unfortunate that, even at this preliminary stage, they sometimes considered their achievements to be very great. I have given all this only to enable people to judge those so-called great Doctors of Divinity, who are said to have attained perfection and are generally accepted as such by the ignorant masses, who judge their worth only by their outward form or elegance.

|